As published in Podiatry Today:

An osteochondral lesion is an injury or fracture to the chondral surface or underlying subchondral bone. These lesions occur in the talus and are generally secondary to single or multiple traumatic events. Traumatic events can cause multiple mechanisms of injury including shearing, fracture, avulsion and compaction. These injuries can result in varying degrees of partial or complete detachment of the chondral fragment.

Osteochondral lesions can lead to underlying subchondral cyst formation. Damaged cartilage can allow a unidirectional invasion of fluid from the ankle joint into the underlying subchondral bone. Over time, osteolysis and subchondral cyst formation occur. As cystic changes occur, the increase in fluid pressure results in increasing pain due to the innervation of the subchondral bone.

These lesions cause ankle joint pain that is associated with weightbearing and activity. Often, patients recognize symptoms in a delayed fashion as the injury generally occurs secondary to other trauma. Generally, the patient presents with an aching ankle months after a prior injury or ankle sprain. Early diagnosis is important as this can lead to improved patient outcomes. Over time, these lesions can impair range of motion, cause stiffness, limit function and also cause catching, locking and clicking of the joint.

Keys To An Accurate Diagnosis

Physical examination should include evaluation of local tenderness and swelling. Assess range of motion to evaluate for pain and limitation as well as clicking or catching of the joint. Frequently, these lesions occur with ligamentous injury and one should thoroughly examine for instability.

One may obtain radiographic imaging to evaluate for cystic or chondral changes, but bear in mind that these studies are insufficient for complete diagnosis. Berndt and Harty developed a classification system for radiographic staging of osteochondral talar lesions. Loomer and colleagues added a stage V to this system, which is important as this stage considers the involvement of a subchondral cyst.

Order magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) when there are incidents of chronic ankle pain. The use of MRI enables the evaluation of cartilage damage, subchondral cystic or edematous changes, and effusions as well as ligamentous assessment. Utilize computed tomography (CT) scans to further determine the true size of the cystic lesion as MRIs can lead one to overestimate bony edema.

What Are The Most Effective Treatment Options?

Non-surgical treatment consists of non-weightbearing and immobilization for approximately six weeks. One can utilize non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and other anti-inflammatory modalities during this time period. Patients should have physical therapy following immobilization to gradually increase range of motion, weightbearing and activity.

After the failure of conservative care, a combination of MRI and CT findings along with intraoperative arthroscopic evaluation are necessary to determine the best treatment option.

Arthroscopy is a key component in treating osteochondral and cystic lesions of the talus. When possible, utilize arthroscopic treatment as this allows for direct visualization of the pathology while avoiding an arthrotomy and potential complication. A wide variety of treatment strategies exist for osteochondral defects of the talus and these treatments and techniques have continued to evolve over the last 15 years.

Treatment options for smaller lesions without subchondral changes consist of excision, excision and curettage, and excision combined with curettage and microfracture (bone marrow stimulation). As a result of bone marrow stimulation, fibrocartilage forms as opposed to hyaline cartilage. Recent studies have shown an 82 percent success rate for the use of bone marrow stimulation in treating primary lesions.

Osteochondral lesions associated with subchondral cyst formation have less favorable results with standard arthroscopic techniques. Additional surgical techniques include retrograde drilling, trans-malleolar drilling, filling of the bony defect with autogenous cancellous bone graft, autologous chondrocyte implantation, matrix-associated chondrocyte implantation, osteochondral autograft transfer system (OATS), and autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis.

Deciding On A Treatment Approach

Base the initial surgical planning on prior imaging studies, prior treatment methods and intraoperative chondral evaluation. Evaluate the size and location of the lesion as larger and more difficult lesions tend to require an open arthrotomy to assist with treatment. Generally, one can treat lesions < 1.0 cm with excision and curettage while larger lesions require grafting of the void. Evaluate the status of the articular surface utilizing standard arthroscopic techniques in an anterior or posterior fashion.

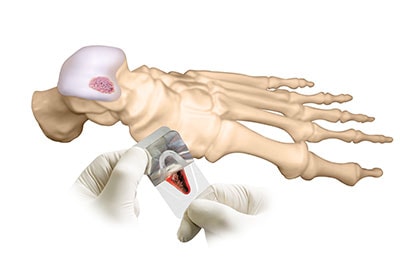

For instances in which the cartilage cap remains intact, retrograde drilling remains an excellent option. Retrograde drilling causes bleeding and an inflammatory response to stimulate new bone formation at the lesion site. This technique brings new vascular access to the area while avoiding damage to the healthy cartilage. One can perform this technique along with grafting or bone marrow aspirate to assist with filling of the void and stimulating growth respectively. While newer techniques involving subchondroplasty systems and techniques have recently emerged, further study regarding the results with these modalities is still pending.

Initial treatment options for lesions with chondral injury are excision, curettage and bone marrow stimulation. Subchondral drilling results in multiple bleeding sites and the release of growth factors. These growth factors form a fibrin clot, which introduces bone marrow cells that result in fibrocartilaginous tissue. For larger lesions, perform autogenous bone graft filling.

One can treat large, chronic, cystic lesions with OATS, mosaicplasty and autogenous bone grafting. Perform these techniques following excision and debridement of the lesion and the underlying subchondral bone. Then harvest these osteochondral grafts and utilize them to restore mechanical, structural and biochemical properties of the initial hyaline cartilage.

Autologous chondrocyte implantation utilizes a two-step procedure isolating chondrocytes from a donor site that are cultivated in a laboratory. One would implant these cultured chondrocytes at the lesion site during a secondary procedure under a periosteal cover in an attempt to regenerate the area with a high percentage of hyaline-like type II cartilage. In a 2009 study assessing the use of autologous chondrocyte implantation in the ankle, Nam and colleagues noted that 91 percent of patients had a “cartilage-like” surface during second look arthroscopy at a 38-month follow-up. Mitchell and coworkers have demonstrated promising results with matrix-associated chondrocyte implantation, and it remains a viable option in the future.

Additional treatment options include cartilage allografts, DeNovo NT Natural Tissue Graft (Zimmer Biomet) and BioCartilage (Arthrex). One can utilize these allografts following initial debridement and drilling of the lesion with or without bone grafting.

A new and promising technique involves autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis. Chondrogenesis-inducing techniques involve repair of the bone-cartilage lesion via a single step procedure that surgeons can utilize for large cystic lesions. While one study shows very good results in the talus after a one-year follow-up, more studies are needed to determine the future role of this modality.

Postoperative treatment involves non-weightbearing for four to six weeks following surgical intervention. The individual procedures require varying degrees of non-weightbearing time periods as well as varying degrees of early range of motion and physical therapy.

In Conclusion

There are multiple treatment options available for osteochondral lesions with associated subchondral cysts and one should determine the best treatment option with the assistance of MRI, CT and intraoperative findings. Utilize retrograde drilling as the primary treatment option when there is intact cartilage. When treating larger lesions, the utilization of allograft and autograft may be necessary. Newer allograft and matrix treatment methods provide promising results, and additional research will help assist and guide future treatment protocols.

Dr. Carter is an attending at the University Foot and Ankle Institute in Los Angeles. He recently completed the Silicon Valley Foot and Ankle Reconstructive Fellowship at the Palo Alto Medical Foundation in Mountain View, Calif.

- Revolutionizing Extremity Imaging: UFAI’s Open MRI for the Foot and Ankle - October 21, 2023

- Youth Sports and Heel Pain: Should Kids Play with Pain? - April 4, 2023

- All About Foot Arch Pain and Foot Arch Cramps - March 15, 2021

Leave a Reply